Review

by Tara Alexander and Sarah Chaney

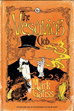

The

press release professes it to be set in the 1890s –

indeed, Amazon (among other places) is still loudly proclaiming

this fact. And so the most important thing to clear up straight

away is: it’s not.

Still,

these mistaken booksellers could easily be forgiven –

were it not for the (albeit numerous) references to the

King, and a minor aside to the first few years of the new

century, the book could very well have been set in the last

decade of Old Queen Vic’s reign. Our hero, Lucifer

Box, you see, belongs part and parcel to the late Victorian

age, where seedy clubs jostled with the moralising of social

reformists, and time had not as yet allowed the Criminal

Law Amendment Act to have much impact on the brothels it

set out to destroy. Where buttonholes were of the utmost

importance and the East End a menace rather than an area

for reform, for the Boer War had not yet pointed out how

much the Empire might actually need the lower classes to

be well-nourished in order to, well, fight!

And

so Lucifer Box seems to live in a kind of vacuum, where

even the most godawful puns are Victorian (fan de cycle

– geddit??) and nothing whatsoever appears to have

happened since the trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895. Why on

earth Mr Gatiss didn’t just give in and set the damn

book in the same year I’ll never understand. Maybe

he thought Sherlock Holmes, whose most interesting cases

were mainly pre 1900, would rather steal dear Lucifer’s

thunder (not that this stops him borrowing shamelessly from

the Adventure of the Devil’s Foot) – but although

both are practiced housebreakers, only Mr Box is an assassin.

Or maybe he felt that he’d already created the perfect

parody of this era in the Chinnery section of the League

of Gentlemen’s Christmas Special”, and wanted

instead to portray Lucifer’s endeavours to be a gentleman

in the early years of a new century, perhaps feeling a certain

affinity for this, 100 years later.

So,

there you have it. Lucifer Box: socialite, aesthete, sometime

artist and, after falling foul of Mr Labouchère in

a rather painful incident off the Bow Road, part of His

Majesty’s Secret Service. Given his mission at the

start of the book by the rather irritatingly named Joshua

Reynolds (a joke must consist of more than simply re-using

a real person’s name and the Royal Academy of Arts,

surely? At least Bella Pok is almost amusing…), Lucifer

quips, puns (and sleeps) his way from London to Naples.

But

I hope my words thus far haven’t been too damning.

There are a few things both myself - and you, dear reader

– should remember. The Vesuvius Club is a work of

fiction, not a treatise on early 20th Century colloquialisms,

so we’ll ignore the over-use of the word “Blighty”

by characters who have probably never been to India.

It is

true that Gatiss wears his influences on his sleeve and

the book is chock full of them. One can see shades of his

favourite James Bond (Dr No) and Doctor Who (The Green Death),

amongst the throwaway references to artists and historical

figures who are contemporary to Mr Box. But the most important

thing to remember is that the novel is great fun. The adventure

is gripping, in a cheerfully exaggerated Boy’s Own

fashion greatly reminiscent of George MacDonald Fraser’s

Flashman – no bad thing. The Vesuvius Club is more

than just another tongue in cheek “Chinnery Jackanory”

story, even if it may seem like that at first. It is well

crafted, fast-paced and ribald. And, while Lucifer’s

self-congratulatory witticisms may grate a little initially,

once he finds someone to temper his behaviour with a little

insolence (the delightful, and very blue eyed, young Charlie

Jackpot), he becomes eminently likeable. Even if historical

adventure novels aren’t your glass of tea, this one

is heartily recommended.

And,

after all, there is nothing more attractive than a man in

top hat and tails…

|